It's easy to miss the real meaning of Daniel Defoe's masterpiece, touted as it often is as the greatest adventure story of all time, one of the earliest modern novels, and possibly the first nonfiction novel. While the first two are true (the third is just wishful thinking), Defoe's novel of a castaway Englishman who learns to survive in the wild is one of the finest depictions of Christian redemption in all of literature.

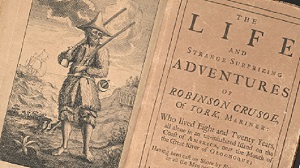

First published on April 25, 1719, Robinson Crusoe was written when the novel was still, well, novel. It introduced many of the devices that came to dominate fictional narrative structures, including straightforward narration and fictional realism. In its first year, it went through four editions because it was so popular, and writers ever since have spoken of being influenced by the book.

While all of those are admirable accomplishments, the real worth of Defoe's novel is spiritual. Crusoe begins in rebellion against his parents and God, but through faithful Bible reading and prayer in his solitude on the island, he becomes a Christian, thus illustrating the need for personal conviction (especially in a land where citizenship involved church membership).

But Crusoe soon realizes the need for Christian companionship and community, and it's not until he converts the island native Friday that he's truly satisfied and happy. The idea John Donne so succinctly expressed in his famous line, "No man is an island, entire of itself," is beautifully illustrated in the spiritual development of the novel's protagonist.

But Crusoe soon realizes the need for Christian companionship and community, and it's not until he converts the island native Friday that he's truly satisfied and happy. The idea John Donne so succinctly expressed in his famous line, "No man is an island, entire of itself," is beautifully illustrated in the spiritual development of the novel's protagonist.

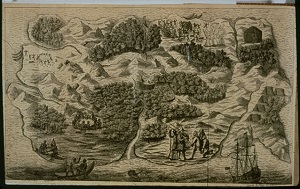

Defoe made no mistake, then, in landing his character on an island. It becomes a metaphor for the spiritual solitude each of us experiences before accepting the truth of Christ's Gospel. At the same time, it illustrates the conditions in which the Holy Spirit works—coming to us not in the craze and busy-ness of everyday life, but in the calm of reflection and through His Word.

Of course, this is also a fantastic adventure story, complete with shipwreck, survival, and battles. Yet to ignore the Christian elements of this story is not to benefit from it the way Defoe intended. A devout Presbyterian Puritan, he wasn't just writing a fun story to thrill bored readers; he was honoring his God through one of the most well-respected works of art in the history of literature.

What Inspired Robinson Crusoe?

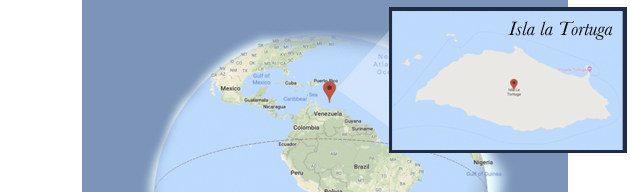

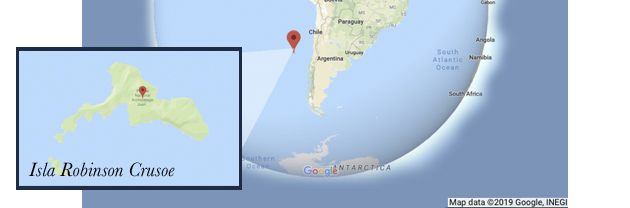

The background and history of Robinson Crusoe is nearly as fascinating as the story itself. It is almost universally acknowledged that Daniel Defoe was inspired by the story of Scottish sailor Alexander Selkirk, who had been marooned for four years and four months at a small island in the Juan Fernandez archipelago, about 400 miles west of the coast of Chile. (In 1966, this island, known to the Spanish as Más a Tierra, was renamed Robinson Crusoe Island to attract tourists; however, Defoe places Crusoe's island near the mouth of the Orinoco river, in Venezuela—possibly the Isla la Tortuga—so the two islands aren't even in the same ocean!).

Selkirk was born in 1676 and went to sea by age 17, in 1693, soon engaging in the life of a buccaneer. Ten years later, he joined an expedition of English privateer and explorer William Dampier. The expedition's two ships, the St. George (commanded by Dampier) and Cinque Ports (Selkirk was sailing master under Captain Thomas Stradling), carried letters of marque, authorizing their armed merchant ships to attack and plunder foreign enemies as the War of the Spanish Succession was then being fought between England and Spain. Dampier was an excellent seaman, but a poor overall commander and his hesitancy and indecision eventually led Stradling to strike out on his own.

But 21-year-old Stradling was an arrogant and contentious captain, and when the Cinque Ports landed at Más a Tierra for fresh water and supplies, he and Selkirk had a falling out. Selkirk had serious concerns about the seaworthiness of the vessel and wanted to make necessary repairs before going on. When Stradling decided to ignore this recommendation, Selkirk stated he would rather stay on the island than continue in the dangerously leaky ship; Stradling took him up on it and marooned him there. (Selkirk's intuition proved correct: Cinque Ports later foundered off the coast of what is now Columbia. While Stradling and some of the crew survived, they were captured and imprisoned by the Spanish.)

In his four years on the island, Selkirk proved resourceful, forging a new knife out of barrel hoops, building huts out of pepper trees, hunting goats (at first with his musket but eventually learning to chase them down!); and making clothes from the goat skins. And like Crusoe, he read and took comfort from the Bible.

In 1709, another expedition, this one led by Woodes Rogers (Roger's ship, The Duke, was interestingly, piloted by William Dampier!), landed at the island and provided Selkirk's long-awaited deliverance. It was Rogers that referred to Selkirk as the "governor" of the island and it was his account of Selkirk's experiences that brought him to public awareness when they returned to England in 1711.

There are indeed similarities between Selkirk's and Crusoe's accounts, but Defoe never said Crusoe was modeled on Selkirk. Defoe was aware of many survival narratives, and most literary scholars now accept that his account was, at least, not Defoe's only inspiration! Other possible accounts include those of Pedro Serrano or Ibn Tufail. And in In Search of Robinson Crusoe, modern-day explorer Tim Severin makes the case that Defoe likely modeled Crusoe more on the surgeon Henry Pitman, who published A Relation of the great suffering and strange adventures of Henry Pitman, Chirurgeon, a short account (just 36 modern typeset pages) with many direct parallels to Robinson Crusoe (his story also directly inspired Sabatini's classic Captain Blood!). Though Pitman wasn't marooned alone, Severin builds a pretty convincing case, connecting Pitman's story to Crusoe's early slavery, life on Isla la Tortuga, and eventual rescue. Severin also looks into the inspiration behind Friday's character, considering a memoir published by Dampier and researching a tribe of Indians (the Miskitos) who accompanied the buccaneers.

About the Editions:

We have heard rumors for years that Robinson Crusoe, being so obviously Christian, has been targeted by editors to have much of that content removed. We were curious how much this was true and so decided to compare as many editions as we could. Click on the comparison chart above to download a PDF of the entire text of Robinson Crusoe with editorial notes from those we looked at.

Robinson Crusoe was written in English, so it needs no translation comparison. But as there have been over FIFTEEN HUNDRED different editions published in the 300 years since its original release on April 25, 1719, it has experienced plenty of editorial tweaking! It was, of course, impossible for us (and impractical for you) to try to compare all of them, so we selected those editions Exodus carries and some of the more readily available (and, in our experience popular) collectible editions from the past hundred years to look at. Our main comparison focused on six vintage editions and two modern editions, but we also looked through several copies used in various Christian curricula.

Robinson Crusoe was written in English, so it needs no translation comparison. But as there have been over FIFTEEN HUNDRED different editions published in the 300 years since its original release on April 25, 1719, it has experienced plenty of editorial tweaking! It was, of course, impossible for us (and impractical for you) to try to compare all of them, so we selected those editions Exodus carries and some of the more readily available (and, in our experience popular) collectible editions from the past hundred years to look at. Our main comparison focused on six vintage editions and two modern editions, but we also looked through several copies used in various Christian curricula.

While we didn't take the time to look at the first edition of Robinson Crusoe for comparison, we chose the edition that can be found on Project Gutenberg to use as our basis for comparison (1919 Seeley, Service & Co. edition by David Price). We had one older version (the 1910 Houghton Mifflin/Riverside Press Cambridge text) available to us, and while there were some differences between the two, they were minimal.

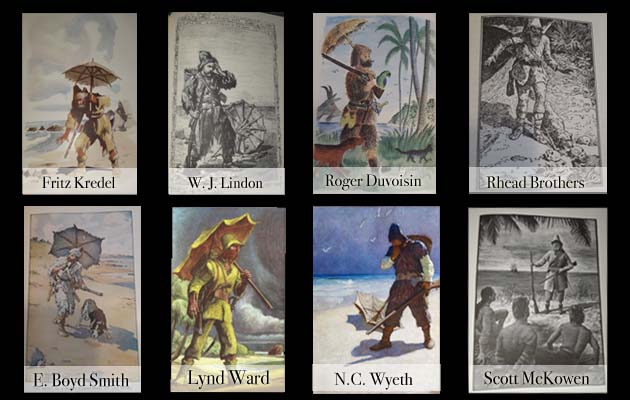

There are several editions commonly sought after, usually because they are part of a series or because of their illustrations, and we list them here:

These are all volumes from series directly targeted to children, and we found it intriguing that most of these are heavily edited—and primarily in the same spots (though Everyman has significantly different editing). However, none are marked "abridged" and their chapter breaks vary considerably. These are mostly from the 1940s-60s, and while the complaint might here be merited (much of the material removed is from Crusoe's meditations and from his explicit evangelism of Friday), to say the Christian element is removed would be far from the truth. Other edits simply tighten up the story, reduce Defoe's constant repetition or clarify passages that might be a little harder to understand for children (who have become the book's primary audience). All of these either cut or heavily abridge the final chapters, detailing Crusoe's experiences after escaping the island. Unfortunately, the 1980s Scribner's, though far less edited throughout, shaves off the entire ending of the book and eliminates everything after Crusoe sets foot in England (interestingly the more recent Scribners edition is complete!).

While the texts may be lacking, the illustrations of these various editions are incredible—Lynd Ward, Fritz Kredel, Roger Duvoisin, the Rhead brothers and, especially, N.C. Wyeth come up with strikingly different interpretations that still manage to bring Defoe's story to life. Apparently, this has been a trend, now, for nearly 300 years—the first illustrations for Robinson Crusoe came out in a 1736 edition! Looking at photographs of other lovely editions of the past may inspire shelf envy! This website has collected visuals of nearly 1500 editions published between 1719 and 1970.

Of the commonly available vintage editions we compared, only the 1946 Doubleday Literary Guild edition was complete (plus, it also includes the Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe!) Though the text is compact, the editors did an impressive job of keeping it clear and readable, and it includes some excellent illustrations by Fritz Kredel (more than the JDE edition has). (Update: we recently encountered the Macmillan Classics edition from 1962; this too is complete.)

Regarding the modern editions: we quickly reviewed the following (we basically spot checked them for known abridgments and found nothing). Here we show the editions we carry, most of which are used by standard home school curricula.

* Ambleside Online recommends editions that have 27 chapters, but offers some assistance for editions that have different breaks.

To answer the question, then: we don't think there is an intention to "de-Christianize" Robinson Crusoe. Originally written for men, it is boys who have traditionally latched on to the story. And editors, especially from the 1890s-1960s tried to make it more appealing for them by either rewriting the book (as in Baldwin's Robinson Crusoe Retold for the Children or Robinson Crusoe in Words of One Syllable) or by cutting out the "slow parts," viz. most of the long meditations about God's mercy and providence. But this trend has not continued. Modern editions are typically complete (unless marked abridged), keeping Defoe's text and worldview intact—even down to the use of the word "negro," the phrase "barbarous savages," and the inclusion of a number of passages that will feel uncomfortable to the modern reader.

Did you find this review helpful?