People tend to think anything unfamiliar must be "old" or "archaic." While it's true that people no longer talk like characters in a Shakespeare play, it is not true that Shakespeare spoke or wrote in Old English. In fact, Shakespeare wrote in Early Modern English, a dialect not very far removed from our own. The main difference between Elizabethan English and contemporary American English is that writers back then understood grammar thoroughly, and we typically understand it not at all.

People tend to think anything unfamiliar must be "old" or "archaic." While it's true that people no longer talk like characters in a Shakespeare play, it is not true that Shakespeare spoke or wrote in Old English. In fact, Shakespeare wrote in Early Modern English, a dialect not very far removed from our own. The main difference between Elizabethan English and contemporary American English is that writers back then understood grammar thoroughly, and we typically understand it not at all.

The confusion gets thicker the further back we look, so that by the time we've reached Geoffrey Chaucer we assume he must be writing in really old English, though in fact he wrote a form of our language called Middle English. Middle English was the bridge between Old English (which to untrained modern readers is incomprehensible) and Modern English (which is what we now speak). That doesn't mean Middle English is easy to read, just that it's not entirely impossible to understand.

English is one of the most disparate languages on the face of the earth. Essentially a Germanic language, it has absorbed elements of Scandinavian languages, French, Celtic, Latin, Greek, and others, mainly due to the coming and going of different people groups through the British Isles. During the 12th and 13th centuries, English went through massive changes, evolving into something far more recognizable to us, and far more distinct in its own right.

By the time Chaucer showed up, English was in a very unique situation. It was more fluid than it had ever been or ever would be, as writers and scholars wrestled with spelling, grammar, and style, shaping the language they had made their own into something established and usable. Because this was a transitional period, Chaucer (who lived 1343-1400) was able to create a unique literary style of his own that became a standard for years to come.

So who was this Father of English Literature? Besides being a poet, he was a philosopher, astronomer, alchemist, and civil servant, whose offices included that of diplomat to Italy. It is in this last capacity that he likely encountered a book by an Italian writer named Giovanni Boccaccio, a compendium of lewd, funny, solemn tales known as The Decameron. Whether he consciously modeled his own The Canterbury Tales on this prior work is unknown, but the similarities are striking.

So who was this Father of English Literature? Besides being a poet, he was a philosopher, astronomer, alchemist, and civil servant, whose offices included that of diplomat to Italy. It is in this last capacity that he likely encountered a book by an Italian writer named Giovanni Boccaccio, a compendium of lewd, funny, solemn tales known as The Decameron. Whether he consciously modeled his own The Canterbury Tales on this prior work is unknown, but the similarities are striking.

Chaucer's work, however, is wholly his own. While he wrote other poems, none made him more famous than The Canterbury Tales, the story of a number of pilgrims making their way to Canterbury to pay homage at a shrine dedicated to Thomas Beckett, the great English churchman. The pilgrims convene at a tavern where the narrator (Chaucer himself) meets them, and the Host of the inn challenges his guests to a contest: each pilgrim will tell two stories on the way to Canterbury, and two on the way back, and the best storyteller will receive a free meal.

What follows is one of the most hilarious, absurd, often bawdy, sometimes devastating, outright rambunctious feats in all of English literature, one that has single-handedly influenced subsequent centuries of writers of all kinds. If you're concerned about your kids reading "adult material," you'll probably want to stay away from these stories, and don't try to substitute with an abridgment—power is mostly in Chaucer's mode of expression.

This isn't to say you won't want to read a translation. For modern readers, though a translation isn't absolutely necessary, it will probably mean the difference between hating and loving the book. Though Middle English isn't that far removed from our own tongue, there's enough to make things difficult for casual or even serious readers, especially if they don't have a background in linguistics or English grammar and structure.

And honestly, you'll want as few distractions as possible while you read this, because the stories themselves are absolutely engrossing. One of the best is The Pardoner's Tale, a story told by a corrupt indulgence-seller about a group of drunken young men who go in search of Death to kill him for taking one of their former acquaintances. The story expertly combines tragedy, horror, rowdy humor, irony, and a solemn implicit observation for an effect that is still just as immediate as it was then.

Scholars have expended millions of gallons of ink (both physical and electronic) examining the religious, political, historical, and literary importance of The Canterbury Tales. These are all legitimate ways of looking at the text, but they tend to overlook a very important element, the one that makes these stories perennially popular: Chaucer wrote with great wisdom and knowledge about human beings.

One of the reasons there's so much bawdiness, sin, death, and just plain bad living in The Canterbury Tales is that Chaucer's goal wasn't to make us feel good about ourselves or to show us the world as it might have been without evil, but to show humans as they actually are. If we think we're any better at heart than the Wife of Bath, the Pardoner, or the Miller, we're deluding ourselves and we've missed Chaucer's whole point.

It should come as no surprise that all these sinners are on their way to a Christian religious site. They're all hypocrites, like the rest of us, and they're all doing something to alleviate their guilt and find some hope. It should also probably be no surprise that, like everyone who misunderstands religion, they're going to the relics of a dead saint rather than to the living God for absolution. Whether Chaucer intended this as the greatest irony or not, it is the irony that lends context to the other ironies.

Books like this always have the disadvantage of seeming relics themselves of a distant past with which we have no real connection. While it's true that the world is in many ways a different place than the one Chaucer knew, the essence of things hasn't changed, especially human nature. While we can read Chaucer to find out about the world he knew, we'd do far better to read him to understand a little more the people that we are.

Review by C. Hollis Crossman

C. Hollis Crossman used to be a child. Now he's a husband and father who loves church, good food, and weird stuff. He might be a mythical creature, but he's definitely not a centaur. Read more of his reviews

here.

ABOUT THE EDITIONS AND TRANSLATIONS

Click here to view and exclusive comparison chart featuring six versions of Canterbury Tales.

To see which of the tales are included in each translation, click on the link to the individual book pages. You will see a chart with all the included stories in red text.

The Norton Critical Edition we carry, edited by V.A. Kolve and Glending Olson is our most scholarly rendering of the Canterbury Tales. It includes all fifteen tales plus the Prologue, as well as extensive source material from the Bible, Boccaccio's Decameron, and various other medieval works. This extra literature shows us various ways Chaucer's first generation of readers might have previously encountered various motifs and stories in the Tales. Kolve also included many critical essays by scholars, which explore the historical background and literary structures of Chaucer. Kolve and Olson kept the "lightly normalized" spelling of Skeat's landmark edition, re-punctuated the text and numbered the lines.Thanks to modern English translations of challenging words printed on each line, the meaning of the story can be grasped by anyone. This a great edition for college students, Chaucer enthusiasts, or high school students who can handle challenging material. All of the Canterbury stories are included here, with the exception of the "Second Nun's Tale" and the "Canon's Yeoman."

The Norton Critical Edition we carry, edited by V.A. Kolve and Glending Olson is our most scholarly rendering of the Canterbury Tales. It includes all fifteen tales plus the Prologue, as well as extensive source material from the Bible, Boccaccio's Decameron, and various other medieval works. This extra literature shows us various ways Chaucer's first generation of readers might have previously encountered various motifs and stories in the Tales. Kolve also included many critical essays by scholars, which explore the historical background and literary structures of Chaucer. Kolve and Olson kept the "lightly normalized" spelling of Skeat's landmark edition, re-punctuated the text and numbered the lines.Thanks to modern English translations of challenging words printed on each line, the meaning of the story can be grasped by anyone. This a great edition for college students, Chaucer enthusiasts, or high school students who can handle challenging material. All of the Canterbury stories are included here, with the exception of the "Second Nun's Tale" and the "Canon's Yeoman."

Donald R. Howard's 1969 edition is very similar to the Norton Critical. Howard mainly referred to the J.M. Manly/Edith Rickert edition, changing paragraph structures and punctuation among other things. While editing the spelling, Howard choose to update as much as he could without giving us "exclusively modern" spellings. Doing this often changes the original pronunciation even more, something which Howard was eager to avoid. Howard writes: "My purpose was not to preserve the appearance of Middle English on the page, nor to enforce a needless consistency, but by eliminating as best I could any nonfunctional old spellings to make a Middle English text which the student or general reader can read with ease and pronounce with accuracy." This edition contains a foreward by Frank Grady, a guide on pronouncing Chaucer, a chronology of Chaucer's life, and a glossary.

Peter G. Beidler published his translation of Canterbury Tales in 1964. At the beginning of the book is an introduction written by Beidler, with a Middle English pronunciation guide and background information on Chaucer, Thomas Becket, Richard II,the Black Death, and the medieval Christian church. Preceding each individual tale, however, Beidler has written up a small introduction and glossary analyzing the characters and plot. Beidler's translation was based on the work A. Kent Hieatt and his wife, Constance Hieatt had produced roughly 40 years before his time. Beidler kept their facing-page translation format, so readers would have the option of switching between the Middle English and our modern dialect.

We carry J.U. Nicolson's 1934 Selected Canterbury Tales in Dover paperback. Aside from a one-page note at the beginning of the book, Nicolson's modern English poetic retelling is not accompanied by any introductions, afterwords, or supplementary material. He does include the Middle English version of prologue at the beginning to give his readers an idea of the original.

We carry J.U. Nicolson's 1934 Selected Canterbury Tales in Dover paperback. Aside from a one-page note at the beginning of the book, Nicolson's modern English poetic retelling is not accompanied by any introductions, afterwords, or supplementary material. He does include the Middle English version of prologue at the beginning to give his readers an idea of the original.

Theodore Morrison's 1975 Portable Chaucer contains the complete collection of tales and Troilus and Cressida. Also included are selections from The Book of the Dutchess, The House of Fame, The Bird's Parliament, the Legend of Good Women. Morrison believes that the worst sin an editor can commit against Chaucer is to make him sound "stuffy or pedantic." His long and thorough introduction with insights into Chaucer's life and writing is another reason by buy this book.

Nevill Coghill's 1951 modern English edition contains all of the tales, as well as a short biography of Chaucer and extensive notes. Unlike many editions of Canterbury Tales, Coghill's version contains the "Canon's Yeoman," one of the few stories believed to be completely original to Chaucer. Coghill's Tales are beautifully understandable, and the text layout and font choices are clean and reader-friendly.

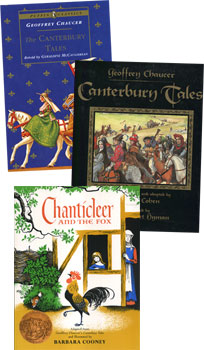

CHILDREN'S VERSIONS

We carry renowned illustrator Barbara Cooney's Chanticleer and The Fox in paperback. It's a magnificently illustrated adaption of the "Nun's Priest's Tale," a morality sketch on the dangers of flattery. Chanticleer is a vain rooster who dreams he will one day fall prey to a fox. He soon forgets his dream, and when a fox approaches him and begs to hear him crow: "Now sing, sir, for holy charity; let's see whether you can sing as well as your father." Chanticleer obliges and naturally at that very moment the fox seizes him. What follows is a tale of trickery and the ultimate escape of Chanticleer, who realizes the folly of listening to flattery. Cooney, who studied illuminated manuscripts and live chickens extensively, used rich golds, reds, oranges, greens and blues to create a certain mood for the story. Cooney achieved what all illustrators aim for: a perfect harmony between pictures and text.

Author Barbara Cohen and illustrator Trina Schart Hyman collaborated to create an adaption of Canterbury Tales, which we normally carry in hardback (currently out of print). The book includes the tales of the Nun's Priest, the Pardoner, the Wife of Bath, and the Franklin's Tale. At the beginning of each story is nearly full-page portrait of the character presenting the tale. Other illustrations are scattered throughout the tales, and most have intricate borders around the edges meant to imitate the illuminated manuscripts of Chaucer's time.

Author Barbara Cohen and illustrator Trina Schart Hyman collaborated to create an adaption of Canterbury Tales, which we normally carry in hardback (currently out of print). The book includes the tales of the Nun's Priest, the Pardoner, the Wife of Bath, and the Franklin's Tale. At the beginning of each story is nearly full-page portrait of the character presenting the tale. Other illustrations are scattered throughout the tales, and most have intricate borders around the edges meant to imitate the illuminated manuscripts of Chaucer's time.

For older kids we carry Geraldine McCaughrean's prose retelling of the tales. This includes the tales of the Knight, Miller, Nun's Priest, Reeve, Scholar, Wife of Bath, Pardoner, Sir Thopas, Franklin, Magistrate, Canon's Yeoman, Friar, and Merchant. Readers have commented on McCaughrean's skill in conveying Chaucer's bawdy humor without being crass. Children ages 9-14 would probably benefit most from this translation, but it is sophisticated enough that older students and even adults might enjoy it. You might enjoy looking up the original version illustrated by Victor Ambrus, though that one is currently out of print.

We also carry Mary Seymour's Chaucer's Stories Simply Told, Chaucer for Children: A Golden Key by Mrs. H.R. (Mary) Haweis (various editions), and the Chaucer Story Book retold by Eva March Tappan

We have continued to add other children's versions to our database as we have come across them, though most are out of print and somewhat hard to find. These include:

When possible, these have links to digital versions on the Internet Archive.

Did you find this review helpful?