To see the text-to-text comparisons, click here.

Banner image by Julek Heller. Click here to view full painting.

Honestly, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is the least King Arthur-y story to come out of Camelot. It's fairly slow moving, there isn't a lot of fighting, and the whole point is that the hero doesn't get the girl. Neither the Black Knight nor the Red Knight make an appearance; instead, they're replaced by a guy calling himself the Green Knight, who's idea of fun isn't hacking away with swords until someone surrenders or dies. His idea of a good time is getting his head cut off with an axe....

....then walking around with it to scare Queen Guinevere and intimidate the knights of the Round Table. It's a pretty bizarre set-up, especially when you realize that the Green Knight doesn't just call himself the Green Knight, he IS the Green Knight. As in, his skin, his hair, his clothes, his horse, etc. are all green. (We aren't told what shade of green, but since this character lives in the woods it's probably safe to assume that it's forest green.)

The Green Knight's identity is hidden for most of the story, but let's just say he shows up in the poem more often than you might assume. And yes, this is a poem, but not the goofy kind of rhyming poem you scribble on your mom's Mother's Day card, or the kind angsty middle schoolers write for their imaginary friends. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is one of the manliest poems you'll ever read, and one of the finest examples of Medieval poetry anybody has ever discovered.

What makes it so manly isn't the story. Sir Gawain is a pretty manly dude, but again, there's a lot less action here than in something like Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur. It's manly because of the way the (anonymous) author uses language. I understand that at a time when meatheads with giant muscles are considered the height of manliness that this requires some explanation, so let me explain.

What makes it so manly isn't the story. Sir Gawain is a pretty manly dude, but again, there's a lot less action here than in something like Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur. It's manly because of the way the (anonymous) author uses language. I understand that at a time when meatheads with giant muscles are considered the height of manliness that this requires some explanation, so let me explain.

Contrary to some popular assumptions, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight isn't a Celtic poem; it actually has more in common with Anglo-Saxon poetry. The author wants his poem to sound a certain way, so he uses hard, strong words that force the reader to pronounce them more strenuously, emphasizing stressed syllables and establishing a vigorous rhythm that calls to mind images of knights on horseback, wild hunting parties, and feasting warriors.

If you're still worried about the lack of action, rest assured: there's plenty here to keep the interest of even the most reluctant readers of Middle Ages poetry. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is basically a really imaginative fantasy story with some slightly confusing allegory thrown in that doesn't matter too much. It's also about true manliness: Sir Gawain is the model of knighthood, both in his desire to serve King Arthur, and in his unwillingness to fall into sin.

Sometimes a book manages to hang on for hundreds of years when there's actually no good reason anyone should read it. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is not that kind of story. It's not just the excellent writing or the fairly kooky storyline that recommend it, however; it's the way the author manipulates those elements to give us a clear picture of the dangers to manhood faced in this world, and the need and means of fighting them.

Sometimes a book manages to hang on for hundreds of years when there's actually no good reason anyone should read it. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is not that kind of story. It's not just the excellent writing or the fairly kooky storyline that recommend it, however; it's the way the author manipulates those elements to give us a clear picture of the dangers to manhood faced in this world, and the need and means of fighting them.

Review by C. Hollis Crossman

C. Hollis Crossman used to be a child. Now he's a husband and father who loves church, good food, and weird stuff. He might be a mythical creature, but he's definitely not a centaur. Read more of his reviews

here.

ABOUT THE TRANSLATIONS

Sir Gawain was written in a Middle English dialect called Northwest Midland, heavily influenced by Welsh and Anglo-Saxon. There were significant differences between English dialects during that period, which is why Chaucer's London Middle English seems so different. We know very little about the author of Sir Gawain, commonly referred to as the "Pearl Poet" (thanks to the title of one of his poems). We do know he was a contemporary of Chaucer, and was probably a nobleman or someone attached to the court given his familiarity with court custom. All of the Pearl Poet's poems, including Gawain, are preserved on the Cotton Nero A.x. manuscript, which dates from around 1400. The anonymity of the poet today is easy to explain, as Tolkien points out: "This poet adhered to what is now known as Alliterative Revival of the fourteenth century, the attempt to use the old native metre and style long rusticated for high and serious writing; and he paid the penalty for its failure, for alliterative verse was not in the event revived."

Sir Gawain was written in a Middle English dialect called Northwest Midland, heavily influenced by Welsh and Anglo-Saxon. There were significant differences between English dialects during that period, which is why Chaucer's London Middle English seems so different. We know very little about the author of Sir Gawain, commonly referred to as the "Pearl Poet" (thanks to the title of one of his poems). We do know he was a contemporary of Chaucer, and was probably a nobleman or someone attached to the court given his familiarity with court custom. All of the Pearl Poet's poems, including Gawain, are preserved on the Cotton Nero A.x. manuscript, which dates from around 1400. The anonymity of the poet today is easy to explain, as Tolkien points out: "This poet adhered to what is now known as Alliterative Revival of the fourteenth century, the attempt to use the old native metre and style long rusticated for high and serious writing; and he paid the penalty for its failure, for alliterative verse was not in the event revived."

How does the Pearl Poet's work differ from the Anglo-Norman styles of his contemporaries? It's best to look at the actual Middle English text to get a feel for his alliteration and bob and wheel structures.

What is bob and wheel, anyway? A metrical device most famously used by the Pearl Poet, bob and wheel is when a very short line (the bob) is followed by a sequence of longer lines (the wheel) which contain their own internal rhymes. The bob essentially connects an alliterative section to the rhyming portion of the stanza. (Example below taken from this page.) Certain letters have been made bold so you can appreciate the alliterative aspect.

And nevenes hit his aune nome, as hit now hat.

Ticius to Tuskan and teldes bigynnes,

Langaberde in Lumbardie lyftes up homes,

And fer over the French flod Felix Brutus

On mony bonkkes ful brode Bretayn he settes

BOB >with wynne,

Where werre and wrake and wonder

WHEEL >Bi sythes has wont therinne,

And oft bothe blysse and blunder

Ful skete has skyfted synne."

Translator Burton Raffel remarks that the "Gawain poet can do an incredible number of things in brilliant style...he can sing like a choirboy or like an angry blacksmith." Unfortunately, we will probably never know exactly who this great poet is. Eclipsed by Chaucer and the rest of the Anglo-Norman poets, his plan to bring back the old Saxon style never really worked. Still, the Pearl Poet's work is very much alive today, and as Tolkien claims, definitely worth reading: "Chaucer was a great poet...but his was not the only mood or temper of mind in his days. There were others, such as this author, who, while he may have lacked subtlety and flexibility, had....a nobility to which Chaucer scarcely reached."

So now that you know a bit about the poem and it's mysterious author, it's time to pick a translation. We currently carry seven here at Exodus—six verse and one prose. Click here to view an exclusive comparison chart featuring these seven different translations.

So now that you know a bit about the poem and it's mysterious author, it's time to pick a translation. We currently carry seven here at Exodus—six verse and one prose. Click here to view an exclusive comparison chart featuring these seven different translations.

Merwin's 2002 translation is one of only two billingual editions we've seen—some readers might enjoy the challenge of trying to decipher the lines of Middle English. Note the word "try"—you'll soon have a new appreciation for Middle English scholars after staring at the original text for a few minutes. "His verse seems closer to oral poetry than the metrical forms that were about to succeed it," translator W. S. Merwin writes in his introduction. "It demands to be heard..." Merwin, who won the 2009 Pulitzer prize for The Shadow of Sirius, approaches Sir Gawain as a skilled poet trained to appreciate sound, color, and robust narrative.

We also carry a Norton Critical Edition edited by Marie Borroff in 1967. Besides Pearl, it includes another poem by the Pearl Poet called Patience. In this poem, the narrator praises the virtue of patience, using the biblical story of Jonah to enhance his argument. Borroff's edition is thorough and includes an introduction, notes, suggestions for further reading, and a guide to the anatomy of rhymed verse. "It has seemed to me," writes Borroff at the beginning of her book, "that a modern verse translation of Sir Gawain and The Green Knight must have fulfill certain requirements deriving from the nature of the original style." Borroff goes on to explain that this means the repetition of many words throughout the story, among other things. She also believes that Gawain should be translated as a fairy tale: "In trying to meet this condition I have incorporated into the translation as many as possible of the formulas still current in the language...many such phrases were too restricted in use to the realm of colloquial speech to be suitable in tone." Her alliterative translation has been considered by many the gold standard for many years.

Simon Armitage's 2008 translation is the second bilingual edition we offer. As a poet trying to harmonize with the original rather than transcribe every last word of it, he does take liberties, but, like Borroff, his alliterative style and ability to juxtapose the contrasts of the poem, brings it to life. As he says, "It is an attempt to combine meaning with feeling. I always intended this to be a translation not only for the eye, but for the ear and voice as well..." This has become a favorite modern translation.

We carry Raffel's 1970 rendering in paperback. Raffel writes in his introduction that he was initially against translating Gawain, until he realized his graduate students could barely decipher it and were unable to really appreciate the story. "As always," Raffel writes, "I have tracked the original as closely as I could....my translation has the same number of lines as does the Middle English poem...the bob-and-wheel at the same points, and it also follows the manuscript division into four parts."

J. R. R. Tolkien's translation of Sir Gawain (not the scholarly edition he published with E. V. Gordon in 1925) was published posthumously in 1975. A professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford, Tolkien was the perfect scholar to interpret this epic that was so heavily influenced by the language he specialized in. In a New York Times Review Poet Edward Hirsch commented that Tolkien's "authoritative edition was a gift to readers," even though today the language may seem a bit "flowery." Tolkien's translation has been well-received by the non-academic community: one Amazon user wrote that "Tolkien's method for these works is unusually readable—most translators sacrifice either readability or meaning; as far as I can tell, Tolkien sacrificed neither." Tolkien also translated Pearl (a shorter poem composed by the Pearl Poet) and Sir Orfeo, written by an anonymous Middle English poet. Both are included in this volume. Sir Orfeo is a retelling of the classical myth of Orpheus, who traveled to the underworld to rescue his wife Eurydice. Merging classical legend with Celtic folklore, the author of Sir Orfeo weaves a story about the king of Thrace who must find his wife Heurodis after she gets abducted by a fairy king. Pearl is a religious poem, and opens with a man mourning his dead daughter, or "pearl." Weeping at her grave one day, he falls asleep. In his dream he finds himself transported to a Eden-like garden where he finds his daughter dressed in majestic white robes. For the rest of the poem they converse about various aspects of the Christian religion such as sin, salvation, the nature of God and heaven. We carry this version in paperback form.

J. R. R. Tolkien's translation of Sir Gawain (not the scholarly edition he published with E. V. Gordon in 1925) was published posthumously in 1975. A professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford, Tolkien was the perfect scholar to interpret this epic that was so heavily influenced by the language he specialized in. In a New York Times Review Poet Edward Hirsch commented that Tolkien's "authoritative edition was a gift to readers," even though today the language may seem a bit "flowery." Tolkien's translation has been well-received by the non-academic community: one Amazon user wrote that "Tolkien's method for these works is unusually readable—most translators sacrifice either readability or meaning; as far as I can tell, Tolkien sacrificed neither." Tolkien also translated Pearl (a shorter poem composed by the Pearl Poet) and Sir Orfeo, written by an anonymous Middle English poet. Both are included in this volume. Sir Orfeo is a retelling of the classical myth of Orpheus, who traveled to the underworld to rescue his wife Eurydice. Merging classical legend with Celtic folklore, the author of Sir Orfeo weaves a story about the king of Thrace who must find his wife Heurodis after she gets abducted by a fairy king. Pearl is a religious poem, and opens with a man mourning his dead daughter, or "pearl." Weeping at her grave one day, he falls asleep. In his dream he finds himself transported to a Eden-like garden where he finds his daughter dressed in majestic white robes. For the rest of the poem they converse about various aspects of the Christian religion such as sin, salvation, the nature of God and heaven. We carry this version in paperback form.

Brian Stone's 1959 version, now in its second edition, is a highly readable translation presented in the traditional format. A reader in English at the Open University and a former journalist in the Middle East, Stone approached Sir Gawain as a lover of the English language, not simply as an academic. Stone himself wrote the informative introduction to his translation, the plethora of notes, and even the interpretive essays at the end of the book. Because of the wealth of helpful content and the readability of the translation, this is an excellent introduction to a beloved Medieval poem. This one is used by Memoria Press with their Sir Gawain Study Guide.

Another Penguin version of Sir Gawain (in addition to Brian Stone's, which was the first), Bernard O'Donoghue's 2006 translation has the lilt one would expect an Irishman to lend the poem. O'Donoghue explains that he chose to render his version in plain modern verse because the "Alliterative Revival" of the original text put more emphasis on rhythmic patterns than on meter or rhyme. The result (which is presented in the traditional format) is a beautiful, immensely readable, and highly enjoyable translation that does no violence to the tone or attitude of the original poem.

Lastly, Jessie L. Weston's 1909 prose translation is available in Dover paperback. The text is broken up into small sections which have their own header, which we find very helpful.This is a very readable (and economical) option. Weston states clearly in her introduction that her translation is meant for common readers, not the medieval scholars: "If by that means they gain a keener appreciation of our national heroes, a wider knowledge of our national literature—then the spirit of the long-dead poet will doubtless not be the slowest to pardon my handling of what was his masterpiece, as it is, in M. Gaston Paris' words, 'The jewel of English medieval literature.'"

CHILDREN'S VERSIONS:

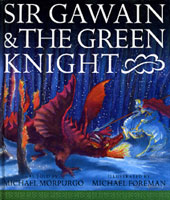

Currently we carry only one children's version of Sir Gawain. Michael Morpurgo published a lovely hardcover Sir Gawain and The Green Knight in 2004, and it is full of Michael Foreman's gorgeous pastel and watercolor illustrations. Unfortunately, this has gone out of print, replaced with a smaller paperback with black & white pictures. In his introduction, Morpurgo writes that although Gawain was honest and noble, "he was headstrong too, and more than a little vain; and as this story will show, sometimes not as honest or true as he would want himself to have been: much like many of us, I think." Kids love to label the "good guys" and "bad guys" in any story they read, but Sir Gawain is a great way to show your children that good men can fail in small ways, and repent. Gawain never really does anything that bad, but he does something bad enough to realize that he wasn't so perfect to begin with.

Currently we carry only one children's version of Sir Gawain. Michael Morpurgo published a lovely hardcover Sir Gawain and The Green Knight in 2004, and it is full of Michael Foreman's gorgeous pastel and watercolor illustrations. Unfortunately, this has gone out of print, replaced with a smaller paperback with black & white pictures. In his introduction, Morpurgo writes that although Gawain was honest and noble, "he was headstrong too, and more than a little vain; and as this story will show, sometimes not as honest or true as he would want himself to have been: much like many of us, I think." Kids love to label the "good guys" and "bad guys" in any story they read, but Sir Gawain is a great way to show your children that good men can fail in small ways, and repent. Gawain never really does anything that bad, but he does something bad enough to realize that he wasn't so perfect to begin with.

If you love the aesthetic of Morpurgo/Foreman books, check out their excellent retelling of Beowulf.

Note: Parents should be aware of the scenes were Bertilak has his wife attempt to seduce Gawain in an effort to test his honor. Gawain doesn't give in, but the text is rather suggestive and one illustration depicts the wife wearing less-than-decent clothing.

Did you find this review helpful?