Click here for the text-to-text comparison.

Humility wasn't a virtue the ancient Greeks cared much about. While they realized raw egotism would eventually get you in a lot of trouble (like Oedipus), they also liked their heroes to have what we'd call attitude. Odysseus, probably the most famous of the Greek heroes, was known for his outsize personality, not his meekness.

We'd like to think we've grown up, that our heroes are more gentle—but are they? Is Rambo more like Jesus than Odysseus, more selfless than Achilles? Of course not: otherwise, First Blood: Part Two would be yawn-inducing rather than cheer-producing. No one wants a hero so humble he can't do his job.

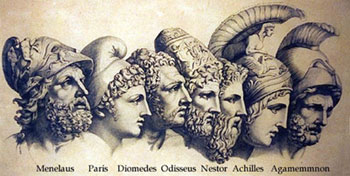

Encountering such helpless heroes isn't something readers of The Iliad need to worry about. First of all, we've got Achilles, the hot headed son of a nymph and King Peleus. He's pretty much bent out of shape throughout the entire story, which begins with his anger against Agamemnon.

Achilles doesn't just get mad, he makes the people around him mad; he even makes the god Xanthos steamed when he fills the god's rivers with the bodies of dead Trojans. The rage spreads all the way to the top of Mount Olympus, where all the gods and goddesses fight among themselves, some in favor of the Trojans, others on the side of the Greeks.

Achilles doesn't just get mad, he makes the people around him mad; he even makes the god Xanthos steamed when he fills the god's rivers with the bodies of dead Trojans. The rage spreads all the way to the top of Mount Olympus, where all the gods and goddesses fight among themselves, some in favor of the Trojans, others on the side of the Greeks.

Besides just anger, there's a lot of fighting in The Iliad. The main conflict is between the defenders of Troy (Ilium) and their Greek attackers who claim Helen was stolen by the Trojan prince, Paris. It's a gory war, ten years long, and though Homer's epic only covers a few weeks, he manages to make them a very bloody few weeks.

All the combat has led some to call The Iliad the world's first war novel, but there's a deeper reason the title makes sense: we don't just see Achilles killing people, we see him becoming more human as a result of the dehumanizing elements of battle reveal his own heart and motivations.

If it's blood and smoke you're after, you'll find them, but chances are you'll be disappointed. Homer isn't praising war, after all, he's showing its dark underbelly. He's also showing us, by way of contrast, how the bestiality of humans can serve to ennoble those who resist descent into barbarism and cruelty.

In the end, we're left with a bit of a sour taste in our mouths. Is Achilles the hero? If so, only because he looks for redemption amid chaos. But it's clear that the "noble pride" the Greeks idolized was empty, and that humility is truly a better way. Whether any of the characters in The Iliad figure that out is something you'll have to decide for yourself.

|

Review by C. Hollis Crossman

C. Hollis Crossman used to be a child. Now he is a husband and father, teaches adult Sunday school in his Presbyterian congregation, and likes weird stuff. He might be a mythical creature, but he's definitely not a centaur.Read more of his reviews here.

|

About the Translations:

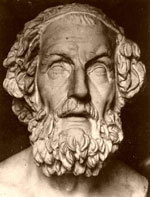

Historians assume the Iliad was written around 800 B.C. Passed down orally, many scholars believe it originated with one single man. However, some believe that “Homer” was a common name for blind travelers who made a living wandering around Greece reciting poetry. Though we no longer live in a storytelling culture, over the years countless translators have given us their own versions of the Iliad—varying in style, tone and length. At least one hundred complete English translations exist today, starting with George Chapman's 1598 translation and including poets like Pope (1715), Cowper (1791), and Bryant (1870) (see a mostly complete list here).

Historians assume the Iliad was written around 800 B.C. Passed down orally, many scholars believe it originated with one single man. However, some believe that “Homer” was a common name for blind travelers who made a living wandering around Greece reciting poetry. Though we no longer live in a storytelling culture, over the years countless translators have given us their own versions of the Iliad—varying in style, tone and length. At least one hundred complete English translations exist today, starting with George Chapman's 1598 translation and including poets like Pope (1715), Cowper (1791), and Bryant (1870) (see a mostly complete list here).

We currently carry six translations here at Exodus. Two are prose versions, and the rest are in poetic form. (Click here to view an exclusive comparison chart which features selections from all six, plus content from Lombardo's translation, no longer carried here.)

The two prose versions are by Samuel Butler (1888) and W.H.D. Rouse (1938). Butler's version is used by the Memoria Press study guide and the SMARR student literature companion. This version is in public domain and can be read online for free. Rouse’s version, not used by any curriculum that we know of, is a more recent novelized Iliad.

Richmond Lattimore's 1951 translation is set in 6 beat lines (hexameter). It is known for being the translation that broke away from the prose Iliads, which tended to dominate during the first half of the century. It is (we're told, not knowing Greek ourselves) the most accurate translation from the original Greek to date, and yet it reads beautifully. One professor at Middlebury College praises Lattimore for "writing in a compact and cautiously rich poetical style but without fussiness." Veritas Press uses this version in their Omnibus IV program, as does Logos School for their six-week Iliad study; it is also Wes Callihan's translation of choice in his survey of The Epics.

Robert Fitzgerald's blank verse Iliad was first published in 1963. None of the curricula here at Exodus requires this translation, but it is a well-respected rendering praised for its readability and elegance, and often recommended by teachers.

Robert Fitzgerald's blank verse Iliad was first published in 1963. None of the curricula here at Exodus requires this translation, but it is a well-respected rendering praised for its readability and elegance, and often recommended by teachers.

Robert Fagles tries to concentrate on the "voices" in his Iliad (1990), believing that readers should hear Homer in their heads and not just process words on paper. Fagles himself was a poet, and his deep appreciation for British and American poetry helped shape his vision for his blank verse Iliad. Peter Leithart favors this translation in his Heroes of the City of Man, an excellent Christian introduction to the ancient classics. One note: Fagles' line numbering does not correspond with the Greek line numbers. Fortunately for readers studying classical Greek, Fagles chose to put the line numbers of the Greek text in parentheses at the top of each page.

Caroline Alexander, author of The War That Killed Achilles, is the first woman to publish an English translation (2015). A classicist, her version offers an introduction which explains the Iliad's significance, looking at historical, cultural, and archaeological evidence, and evaluating it on its literary merit. While the introduction is specialized, it's not too hard of a read for the layperson. Her translation itself preserves the line numbers with the ancient Greek and her style is quite appropriate to the epic poetry form, "simultaneously artificial and action-oriented. It reads like a performance."

Stanley Lombardo's verse Iliad (1997) is a fast-paced translation which is wonderful for reading aloud. Professors have praised him for making the Iliad more accessible to students who don't have the time or patience to wade through weightier versions.

There are other, more recent, translations of the Iliad, and it will likely remain a favorite translation project of Greek scholars for centuries to come. Whichever version you choose to read, we hope you'll enjoy the epic story.

Children's Versions:

If you're hoping to introduce your younger students to The Iliad, we recommend starting with an adaptation for children. We have four that we believe are excellent. The Iliad for Boys and Girls, by Alfred J. Church, is one such option. Church's book is a solid, literary retelling which manages to cover most of the adventures found in the original. This version was written in the late 19th century and has the advantage of being available online for free. This book contains a few black-and-white illustrations, and has large-sized font.

If you're hoping to introduce your younger students to The Iliad, we recommend starting with an adaptation for children. We have four that we believe are excellent. The Iliad for Boys and Girls, by Alfred J. Church, is one such option. Church's book is a solid, literary retelling which manages to cover most of the adventures found in the original. This version was written in the late 19th century and has the advantage of being available online for free. This book contains a few black-and-white illustrations, and has large-sized font.

Padraic Colum’s Children’s Homer combines stories from the Iliad and the Odyssey into one book. Written during the 1940s, this version is a little more accessible and also available online. Includes delightful pen-and-ink illustrations by Will Pogany. Colum spends the first part of the book retelling how how Odysseus' son Telemachus went on a voyage and heard the tale of Troy from Menelaus and Helen. The second part details Odysseus' travels and his triumph over the wicked suitors when he returns home.

We also carry Rosemary Sutcliff’s Black Ships Before Troy, which is an excellent rendering of the Iliad for kids.We carry two versions of this book, an inexpensive paperback and an incredible hardcover, lavishly illustrated by Alan Lee (of Lord of the Rings fame). Lee says this about his technique:

“I like to work in watercolor, with as little under-drawing as I can get away with. I like the unpredictability of a medium which is affected as much by humidity, gravity, the way that heavier particles in the wash settle into the undulations of the paper surface, as by whatever I wish to do with it. In other mediums you have more control, you are responsible for every mark on the page — but with watercolor you are in a dialogue with the paint, it responds to you and you respond to it in turn. Printmaking is also like this, it has an unpredictable element. This encourages an intuitive response, a spontaneity which allows magic to happen on the page. When I begin an illustration, I usually work up from small sketches — which indicate in a simple way something of the atmosphere or dynamics of an illustration; then I do drawings on a larger scale supported by studies from models — usually friends — if figures play a large part in the picture. When I've reached a stage where the drawing looks good enough I'll transfer it to watercolor paper, but I like to leave as much unresolved as possible before starting to put on washes. This allows for an interaction with the medium itself, a dialogue between me and the paint. Otherwise it is too much like painting by number, or a one-sided conversation.”

Sutcliff's text is substantial, so don't mistake it for a "5 minute read" that you can skim before bedtime. It's supposed to be the kind of picture book that will last a while as you immerse your kids in a good story. The aim of children's literature should be to lay the proper foundations for an adulthood of reading, and Sutcliff definitely did her part.

We also offer occasional used copies of the Kingfisher Epics Iliad retold by Nick McCarty and illustrated by Victor Ambrus.

And don't forget to check out Bellerophon Books' Coloring Book of the Trojan War: The Iliad Vol. 1 and Vol. 2. Full of full page action scenes (mostly taken from ancient Greek vase painters) text by Berkley professor John K. Anderson, and actual Greek lines from Homer gleaned by Professor Apostolos Athanassakis, they would make a wonderful supplement to your ancient studies curriculum!

Did you find this review helpful?